The Strong Families Fund: Outcomes-Driven Resident Service Coordination

The need for quality affordable housing is large and growing: 54 percent of families pay more than half of their monthly income on rent. Having a stable, safe place to live that doesn’t cost an entire paycheck is crucial to low-income Americans participating fully in the economy. Beyond that fact, research also shows strong physiological connections between poverty and toxic stress and health outcomes for children and families. In one distressed ZIP Code in St. Louis, 52.5 percent of families live in poverty. A child born and raised here is expected to live only 69 years — ten years below the national average, per a PolicyLink report.1 And children born into poverty usually stay there; data show children born into the bottom quintile in terms of family income have only an eight percent chance of moving to the top quintile.2

Research also shows that outcomes can improve when a social service coordinator is available to families living in affordable housing. This coordinator helps connect residents to services onsite and in the community, including transportation, banking and financial coaching, food, quality early childhood programs, children and youth educational and enrichment programs, health care, job skills and workforce training — you name it. These coordinators also increase the social cohesion of affordable rental property communities, creating opportunities for people to engage in community activities, rely on and learn from their neighbors, and experience less isolation along the way.

So we know families thrive with access to better supports that connect them to a range of services that can help them obtain successful employment, education, and health outcomes. But service coordinators are generally paid for through cash flows generated by the property, grants secured by the developer, or agreements with third-party service providers. Long-term, stable funding for service coordination is elusive. That’s why The Kresge Foundation’s social investment practice team began to hunt for a solution through a pay-for-performance investment.

The road to this innovative investment opened only after Kresge’s human services team, in response to growing demand from the field to enhance the quality and resources available to tenants in affordable housing, first made a grant to the Stewards of Affordable Housing for the Future to develop new metrics related to outcomes for low-income housing residents. It was the first attempt to create a standard “menu” of metrics for multiple developers to use to assess the link between their housing developments and the outcomes of the people living in them. It included performance measures from income and assets, health, housing stability, community engagement, and education. It would become a crucial underpinning of our pay-for-performance work, giving us the firm data and consistent reporting criteria — across developers and developments — to assess outcomes and make a larger argument about the cost-effectiveness of service coordination.

With that matrix in hand and the desire to put it to use, we centered on our guiding question: How could a fund be structured to incentivize developers and investors to invest not only in building housing units but also to implement high-quality, outcomes-driven service coordination?

The result was the Strong Families Fund, a Kresge–led, multi-partner effort to fund up to ten years of resident service coordination in Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC)–financed family housing through a pay-for-performance, incentivized loan structure. In a LIHTC deal, a developer applies for, and is awarded by a housing finance agency, a certain number of tax credits for an affordable housing project. The developer then takes those credits to a bank or other investor to sell a partnership interest in the project, to get the upfront capital needed to build the development. The banks (now partners) use the tax credits to offset future federal taxes (and in some cases, meet their obligations under the Community Reinvestment Act), saving themselves on next year’s tax bill, while the developer now has the cash on hand to construct or rehabilitate the property. The developer agrees to keep the property affordable for 15 years. Using pay-for-performance mechanics, the Strong Families Fund was built to provide LIHTC developers a ten-year funding source for resident service coordination when there is evidence that resident outcomes are tracked and are improving.

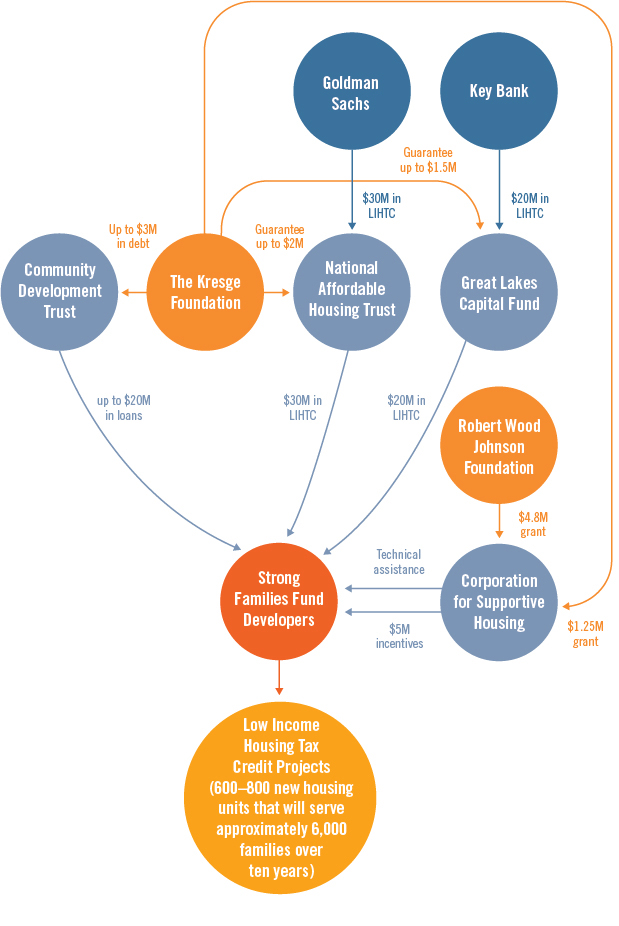

The Strong Families Fund, which closed in 2015, proposed to include $50 million in tax equity from Goldman Sachs and Key Bank, along with grants, guarantees, and loans from Kresge and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Kresge invested in four organizations participating in the fund: a $2 million guarantee to the National Affordable Housing Trust and a $1.5 million guarantee to Cinnaire, Inc., both syndicators of LIHTC equity; a $3 million program-related loan to Community Development Trust, a community development financial institution (CDFI) and the provider of permanent financing; and Kresge’s human services program made a $1.25 million grant over three years to the Corporation for Supportive Housing, also a CDFI, which would provide technical assistance and support the fund’s operations. To support “performance payments” to developers, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation will make up to $5 million in grants available.

To generate a funding source that would enable developers to consistently provide high-quality service coordination, the effort called on using the following levers:

- The release of three months of the operating deficit reserve (and replacement with the Kresge guarantee) to pay for service coordination in years one and two;

- Up to $90,000 annually in performance payments to developers in years three through ten; and

- An additional equity payment from the LIHTC investor to the developer in year ten if outcomes are achieved.

Projects that received investment agreed to establish baseline measures at the start, implement a data-driven service coordination program in collaboration with the Corporation for Supportive Housing, and report on the results annually. Developers are required to report the resident data and, if outcomes improve, will earn a performance payment up to $90,000 annually for ten years — funded through grants from Kresge and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Figure 1. Strong Families Fund

Reaching agreement with so many parties required enormous perseverance and commitment on the part of many. Everyone was optimistic about the opportunity to influence the field and improve outcomes for families. Going in, we thought the Strong Families Fund would finance up to eight projects, generating 600 to 700 new units of service-enriched housing. We believed then, as we do now, that through an outcomes-oriented development, we could strengthen the connection between better service coordination and improved resident and property outcomes. We also hoped to create a business case to attract housing finance agencies, private investors, or other public agencies to step up to provide the incentive payments — after seeing the data demonstrating the cost-effectiveness of such an approach.

Less than two years in, we have some lessons learned and an emerging question to wrestle with: Were we a little too early, a bit ahead of the market, to test this model?

The developers involved were all financially and operationally strong, they were all mission-driven, and most had participated in the creation of the outcomes menu. This group was advanced in its understanding of how to operationalize service coordination. The first challenge was reaching consensus about what measures were meaningful and could be tracked accurately and consistently at a series of properties owned and managed by different developers.

It made sense to work with the strongest affordable-housing developers. But unexpected challenges soon emerged. Because of their relative strength, these developers can command very high equity pricing for their LIHTC deals — in some cases, higher than what was offered through the Strong Families Fund. And, although it offered additional financial benefits via the performance payments, developers often saw it in their best business interests to get the highest equity pricing possible at closing and not take a chance on the performance payments down the road. It’s basically like this: If I offered you $100 for running a mile now or $130 in three years, but only if you improved your time in the mile each year, which deal would you pick? Although these developers are undoubtedly committed to the principles of service coordination, we realized there is a lot of truth in the adage “cash is king.”

These challenges led to a slower-than-anticipated deployment of the Strong Families Fund’s capital. By the end of 2016, only three transactions had closed. All parties involved discussed whether there was still enough to be learned from the experiment. Ultimately, we believed three more properties were in the pipeline and would close in 2017.

And then we had an election.

With the new administration, uncertainty hit the markets as all waited to see what the election results would mean for so many related areas of work. Early on, there was one area with a high degree of clarity: Throughout the 2016 presidential campaign, conversation centered on tax reform and, specifically, cutting the corporate tax rate. Minimizing a company’s federal tax liability is the primary reason that banks and corporations invest in the LIHTC market. Banks are also motived by receiving Community Reinvestment Act credit for their investments in LIHTC projects. With the prospect of lower taxes and reduced value of the credits to corporations, the market for tax credits slowed considerably, even before the new president took office. In some cases, transactions can still be financially viable — even with lower equity prices — but others will need to find capital resources to fill the funding gaps. Although the Strong Families Fund partners are optimistic that the remaining three deals will close, the outcome for the winter of 2017 is less certain.

So back to our question: Were we too early for this model? And what lessons can we offer to others? There is plenty to be learned about what to do and what not to do when trying to introduce a new pay-for-performance element into an established market, such as LIHTC equity. We clearly had assembled the right panel of partners who were all aligned around the goals and ambitions of the Strong Families Fund. However, we had not assessed the business drivers of those partners fully, and that proved to be an unexpected and high hurdle. We also learned that new products and fund structures take much longer to be accepted in the marketplace; development projects tend to take at least two years to get online. And, we learned that you never know for sure what significant political-context changes are coming or how they might impact the market.

Is the Strong Families Fund worth the investment and the effort? In terms of outcomes, the initiative, at a minimum, will collect and understand resident and property data outcomes for residents in 370 units across three affordable housing developments, with the potential for data from an additional nearly 520 units as more transactions close. We don’t regret investing our capital toward this effort and are waiting to see if that investment can produce the impact we truly wanted to make.

There are also positive lessons we see now. The Strong Families Fund has given momentum to establishing a uniform set of metrics in the affordable-housing sector, to the value of connecting residents to services, and to the importance of finding a predictable funding source for service coordination. Development and testing a protocol for data collection remains a fruitful and positive idea in an increasingly outcomes-driven market.

If we want the housing sector to strive not only to produce units but also to improve residents’ lives, we need policies, public agencies, and nonprofit and for-profit developers to focus as intensively on outcomes as they do on the costs of “sticks and bricks.” Over the next ten years, the Strong Families Fund will be able to tell a data-driven story of exactly how far six developments and their residents have gone toward achieving that goal.

1 Kalima Rose and Teddy Ký-Nam Miller, “Healthy Communities of Opportunity: An Equity Blueprint to Address America’s Housing Challenges,” Policy Link (2016), available at http://www.policylink.org/sites/default/files/HCO_Web_Only.pdf.

2Raj Chetty et al., “Where is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States” (June 2014), available at http://www.rajchetty.com/chettyfiles/mobility_geo.pdf.