Paying for Results: Reforming How the Public Sector Funds Social Services

A quiet revolution is taking hold across the United States. Faced with diminishing budgets and a rising demand for social services, governments at every level are adopting innovative funding models to protect against waste and ineffective programs while improving outcomes for the people they serve.

In the wake of a child welfare crisis in 2006, Tennessee adopted a new model to reduce the amount of time it takes to place children in permanent homes. Research indicated that reducing the time a child spends in a temporary home would not only lead to better outcomes for the child but also decrease costs in services and their administration later on. With this in mind, Tennessee implemented a new contract that sought to transform its child welfare system. The terms were relatively straightforward: Providers that improved on baseline performance received a share of the state’s savings, and those that performed worse than the baseline reimbursed the state for cost overages. Once fully implemented in 2010, Tennessee’s new model nearly cut in half the average time a child spends in temporary care, from more than 22 months to 14.1

Tennessee is part of a wave of governments and other funders looking for new and better ways to have an impact with increasingly scarce resources. By re-engineering the way it traditionally delivered services, the state was able to improve the lives of some of its most vulnerable populations while saving taxpayer dollars. The state employed just one of a growing number of outcomes-based funding models that hold immense promise for transforming the way governments deliver services and improve the lives of their citizens.

This chapter outlines the challenges of traditional funding models and how results-based funding improves on them. It also covers different types of results-based funding mechanisms and considerations for selecting and designing these mechanisms. It reviews the benefits, weaknesses, and challenges to using results-based funding models as well as the potential for widespread adoption of these innovations.

MISDIRECTED INCENTIVES OF TRADITIONAL FUNDING MODELS

In traditional funding models, governments and the social sector primarily focus on providing a prescribed set of services or activities. For different reasons, these efforts often fall short of delivering on the outcomes that funders want, and they do not always help the beneficiaries. One potential reason for this is that traditional funding models do not lend themselves to knowing which programs work and which do not. Instead, the model focuses on compliance and performing prescribed activities. Bureaucratic inertia can compound the problem. Organizational or legislative resistance to change leads to programs getting funded the same way year after year, regardless of impact.

The second hurdle centers on rigid and misaligned funding streams, or what some call the “wrong pockets” problem. Sometimes, the entity that fronts the cost of implementing a program does not receive commensurate benefit.2 For example, one government entity may know of a cost-efficient, evidence-based intervention or program that produces better outcomes. However, the majority of the resulting savings may accrue to different government entities. Therefore, the first government entity would bear the cost of implementation and have little incentive to pursue the program. This challenge dissuades that entity from carrying out a program that would improve lives and save money.

However, change is coming. With a growing emphasis on evidence-based practices, data-driven decision-making, and fiscal accountability, governments and the social sector are redoubling efforts to identify and support programs that work. Funders, too, are devising new and creative ways to get around the wrong pocket problem. For example, the U.S. Department of Education, as part of its Performance Partnerships Pilots, has launched initiatives to “braid” (strategically coordinate separate programs and funding streams) and “blend” (consolidate funding streams from separate programs) funding to increase the success of disconnected youth in achieving educational, employment, wellbeing, and other key outcomes.

IDENTIFYING, MEASURING, AND PAYING FOR RESULTS

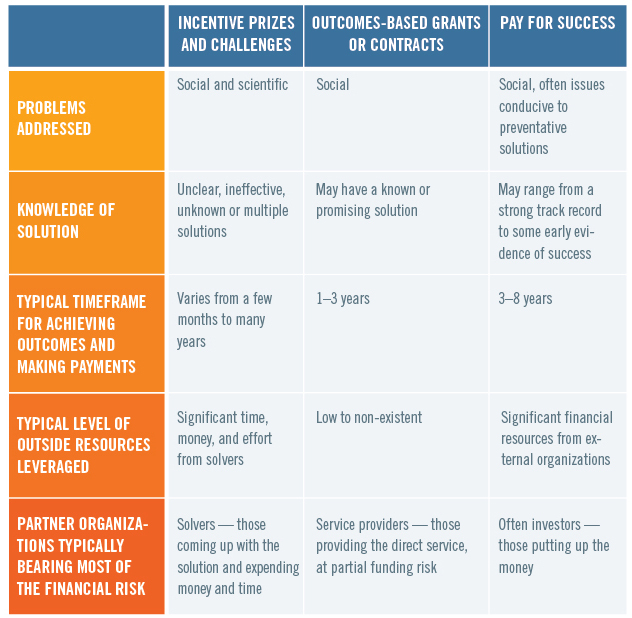

No longer interested in paying for compliance, governments and other funders are shifting the focus to identifying, measuring, and evaluating success. Funders also now have many distinct tools to deploy based on the unique circumstances of the challenge or social policy to be addressed. We focus on three of the most promising models: 1) incentive prizes and challenges, 2) outcomes-based grants and contracts, and 3) Pay for Success. (See Figure 1 for a summary of the models.)

Incentive Prizes and Challenges

Incentive prizes and challenges are competitions among individuals, groups, or other entities designed to achieve clear, defined goals in a defined time frame. In a challenge, the funding organization identifies a problem, creates and publicizes a prize-based challenge for solving that problem, signs up diverse participants, and offers a reward to the winner. The funding organization awards the prize funds to the solver(s) with the best solution that achieves the desired outcome.

Outcomes-Based Grant or Contract

Outcomes-based grants or contracts are bilateral agreements between a payer and service provider(s). Under the arrangement, service providers receive some funding from the payer to operate the program, and they receive additional performance payments if they achieve agreed-on outcomes. (The proportion of total funding that additional payments make up can vary significantly.)

Pay for Success

Pay for Success projects, also known as social impact bonds, are contracts that enable a funder, typically government, to pay only when the program achieves desired outcomes. An external organization assumes responsibility for delivering outcomes. If (and only if) the outcomes are achieved, the funder releases an agreed upon amount of money to the external organization. Often, external organizations raise money from investors to fund service providers who work to achieve the outcome.

Figure 1. Three Models for Outcomes-based Funding

CHOOSING A RESULTS-BASED FUNDING OPTION

Not all results-based funding mechanisms are suited for all social policy objectives. When considering which innovation to use, governments and funders should closely examine the challenge they wish to address and consider several factors before selecting a specific instrument. We recommend considering four factors: 1) the nature of the problem, 2) the track record of solutions or potential solutions, 3) the time frame for achieving outcomes and making payments, and 4) the typical level of outside resources and partner organizations involved. Each of these considerations is important to identifying the most effective tool.

Nature of the Problem

Nearly every results-based funding mechanism is designed to address social problems. However, within the social arena, some tools are better suited for certain types of social problems, and a few can be used for nonsocial issues. For example, incentive prizes and challenges, which seek to galvanize people outside the funding organization to develop innovative solutions to vexing challenges, tend to be more flexible in that they can be used for social and scientific challenges. In contrast, Pay for Success and outcomes-based grants or contracts tend to focus exclusively on social problems, with the former placing a greater emphasis on preventive interventions and solutions.

Knowledge of Solution

Whether effective solutions have already been identified and tested affects the tool selection process. Some tools are suited for discovering or devising new solutions, while others encourage and reward the implementation of proven or promising interventions. Many fall somewhere in between testing and scaling. The incentive structure of prizes and challenges allows for multiple solvers and multiple answers to a challenge. Given that prizes and challenges are meant to devise solutions for particularly complex and intractable problems, no previous solution or intervention need exist. In contrast, Pay for Success is made practical (and practicable) by the existence of a solution, the track record of which may range from promising to proven. Because the financial risk of Pay for Success projects is high, external organizations and investors tend to want or require interventions that have a high likelihood of achieving results.

Outcomes-based grants or contracts tend to require something between prizes and challenges’ “white space” and the effective interventions of Pay for Success. In outcomes-based grants or contracts, a known or promising solution may not exist, although having an existing promising solution tends to lead to better results. In the Tennessee example above, service providers could have either implemented a promising or proven intervention to achieve the performance targets or devised their own approach in hopes of meeting the targets. Similarly, managed care and outcomes-based contracts are designed to encourage practitioners and service providers to adopt activities and behaviors that are shown to lead to certain outcomes but leave room for service providers to innovate and test new interventions.

Time Frame for Achieving Outcomes and Making Payments

Another consideration is the timeline. On one end of the spectrum is incentive prizes and challenges, which can take as little as a few months to structure, implement, and pay out (although they can take years to complete). Loan incentives, investment tax credits, and performance-based contracting also tend to be quicker to structure and lead to change on shorter timelines.

Outcomes-based grants or contracts typically last between one and three years. Because they are often modifications to existing government grants that provide base funding and incentives based on performance, the timeline of outcomes-based grants and contracts tends to mirror that of traditional funding models and government contracts.

Meanwhile, Pay for Success arrangements typically last between three and eight years, although there are exceptions, such as the Chicago early childhood education project, which is slated to run 17 years. The typical three-to-eight-year timeline is driven largely by financial considerations; Pay for Success must balance the time needed to prove or disprove the efficacy of an intervention (and achieve results) and the time that investors and funders are willing to tie up money before receiving payment.

Outside Resources and Partnerships

Another important distinction between the various types of results-based funding is the degree to which external partners are engaged in the process. For funders, it is critical to determine to what extent outside resources are needed and desired to solve the problem. Although collaboration across levels of government and sectors is almost always necessary, the degree to which external partners contribute resources and are involved in program implementation will vary. Given the significant investment required for creating and managing partnerships, funders must weigh the benefits, limitations, and appropriateness of engaging external resources to meet their objectives. In addition, the specific ways that funders (particularly government agencies) can leverage external resources may vary by state on the basis of legislation and other regulations.

On one end of the spectrum are Pay for Success projects, which require a high degree of resources from external stakeholders. The most obvious resource requirement is the external financial resources typically used to pay the implementation partner conducting the intervention. In the United States, private investors, philanthropies, and even nonprofit organizations have all contributed financial resources to Pay for Success deals. For many funders, one or more partners are required to fill knowledge gaps related to innovative finance, monitoring and evaluation, stakeholder management, or other issues.

Perhaps even more important than the financial commitment is the investment of time required from all stakeholders. Pay for Success is still a fairly new concept, and each deal requires a highly tailored agreement that aligns the objectives of each group. The deals can take from several months to more than a year to craft, and they require a high level of commitment and coordination from all stakeholders.

As mentioned earlier, the very nature of the problems that incentive prizes and challenges are best at tackling lends itself to involving multiple stakeholders. The problem solvers in particular must invest significant time and potentially money in developing solutions. In addition, funders may work with other organizations to identify potential solvers and promote participation. They may also seek out partner organizations to provide financial and advisory resources for the planning and design phase of a challenge as well as contributions to the award.

The external resources required for outcomes-based grants or contracts are comparatively low. As discussed above, the social issues addressed by this type of results-based funding are more clearly defined. As such, funders may only need to engage an implementation partner who will be paid on the basis of his or her success.

SHARED CHARACTERISTICS OF FUNDING MODELS

Delivering Greater Impact

Although the considerations in determining the most suitable tool for a given challenge vary, the benefits of these tools are similar. The most important is, of course, the impact on a given population or issue area. One of the principal benefits of outcomes-based funding is that it allows government and other funders to differentiate between programs that are providing value to beneficiaries and those that are not. By requiring programs to meet established outcomes for a target population and then rigorously testing programs’ abilities to achieve those goals, funders have the data to make decisions about where to channel resources for the highest impact.

Sharing and Shifting Risk

The structure of many results-based funding mechanisms offers funders the opportunity to share or even shift financial risk. In the case of outcomes-based contracts, government or foundations are able to share the risk of success or failure with the service provider. If a provider does not successfully meet the objectives of the contract, the provider may forfeit a bonus or may not receive a portion of the agreed upon contract value. In the case of Pay for Success projects, the government does not incur any costs should a program not meet the outlined objectives and targets. For incentive prizes, government shifts the costs of developing innovative solutions to the problem solvers (although there may be some sunk program management costs). When choosing between mechanisms, funders should consider their appetite for taking on financial risk.

The “failure” of the first Pay for Success initiative in the United States, New York City’s Adolescent Behavioral Learning Experience (ABLE) intervention, demonstrates the success of outcomes-based funding. The ABLE project did not meet the targets established by the city of New York and agreed on by the investors, philanthropic partners, and the service provider. As a result, government paid nothing for the intervention. This left the city with the ability to channel resources to more proven interventions or to experiment with another innovative solution.

Greater Financial Stewardship of Scarce Dollars

A focus on results also means that government and philanthropic resources are spent in a more responsible and meaningful way. In an era of tighter budgets, results-based contracts and other “pay for results” tools allow funders to ensure greater social value for every dollar spent. In the case of services that prevent a more costly intervention, paying for outcomes may actually mean paying less in the long run.

Reduced Administrative Burdens

A results approach also lowers administrative costs. As discussed, the current model of grant or contract management focuses heavily on monitoring who does what and how, rather than on what they achieve. This focus requires funders to spend a great deal of time monitoring various activities and arbitrary indicators of compliance, placing a significant administrative burden on agencies.

CHALLENGES TO TRANSFORMING THE STATUS QUO FUNDING MODEL

To make this transition possible, funders must invest significantly in developing the capacity to monitor and evaluate the programs. This will require not only training, the creation of new tools, and the development of new business processes, but also a fundamental shift in the way administrators think about funding. For government, this would require both steps taken at the executive level and the alignment of other powerful actors, including the legislature and government administrators. Despite the significant investment in resources and time, a shift from an administrative to an outcomes focus would pay significant dividends for both funders and beneficiaries.

Additionally, as with any system that awards funding, there is the potential for manipulation of programs or data to give the appearance of meeting outcomes. It is possible that some programs may seek to channel services only to those most likely to succeed, leaving out those who are most at-risk and often have the most need. This would be a perverse incentive that lowers the social value of funding. In addition, without the ability to substantively monitor and evaluate programs, it is possible that results could be manipulated to demonstrate outcomes that have not been achieved.

SCALING RESULTS-BASED FUNDING

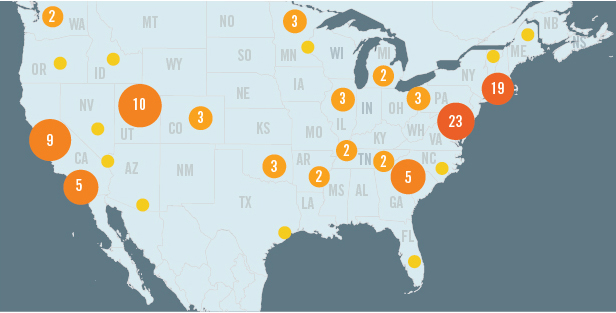

Despite the challenges, outcomes-based funding is once again the focus of governments and philanthropic funders across the country. Several Pay for Success initiatives have been launched. (See Figure 2 for a map of Pay for Success activity in the United States.) Large philanthropic funders like the Annie E. Casey, Laura and John Arnold, and Bill & Melinda Gates foundations (to name only a few) have also changed how they think about grant making, with a renewed focus on demonstrated outcomes for continued funding.

Figure 2. United States Pay for Success Activity Map.

Source: Nonprofit Finance Fund Pay for Success Learning Hub, available at https://nff.org/invest-in-results.

Note: Activity includes projects, legislation, and opportunities to support Pay for Success efforts.

Most important, the infrastructure required to scale up outcomes-based funding is improving. The body of evidenced-based interventions is growing. Organizations such as the Washington State Institute for Public Policy (WSIPP) have created databases of evidence-based interventions, which funders can use to determine which issue areas might be ripe for scaling their outcomes-based funding portfolios.

An important step to leveraging this growing body of evidence will be to develop a common language for describing outcomes and measuring performance. In the impact investing field, initiatives such as IRIS and the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board are attempting to codify what impact means for investors. Similar initiatives would offer funders the opportunity to speak with one voice and reduce the monitoring and evaluation burden for all parties.

1Beeck Center for Social Impact & Innovation, “Funding for Results: A Review of Government Outcomes-Based Agreements,” Georgetown University (November 2014).

2John Roman, “Solving the Wrong Pockets Problem: How Pay for Success Promotes Investment in Evidence-Based Best Practices,” Urban Institute (September 2015).