Outcomes Rate Cards: A Path to Paying for Success at Scale

Consider Jason and Emily, two young people living in the north of England. Jason, from just outside Liverpool, struggled to find employment, even after completing his Level 1 plumbing training.1 Emily, from Manchester, was in danger of dropping out of school without graduating; she lacked self-confidence and a sense of responsibility.2 Both were at risk of becoming “NEET” (not in employment, education, or training),3 but they faced their own unique challenges.

Fortunately, Jason and Emily were each connected with programs that met their individual needs. For Jason, this was a program called Career Connect, a nonprofit organization that provides career-focused support for disadvantaged 14- to 19-year-olds.4 For Emily, it was Teens and Toddlers, a nonprofit organization that runs an 18-week mentoring program pairing teenagers from disadvantaged communities with toddlers in nurseries.5

Though they didn’t know it at the time, Jason and Emily were able to change their lives for the better as a result of the world’s first outcomes rate card, developed by the United Kingdom’s Department for Work and Pensions.

An outcomes rate card is a list of outcomes government wants to achieve in order to advance its policy priorities, and the monetary value (i.e., price or rate) it is willing to pay for each outcome. A government entity uses the rate card as the basis for a procurement process. The selected service providers receive payment only when the stated outcomes are achieved and participants’ lives are positively affected.

A NEW APPROACH TO A PERSISTENT PROBLEM

In the United Kingdom, as in many parts of the world, young people have faced barriers to employment and limited access to high-quality educational training programs in the wake of the Great Recession. In the first months of 2016, 865,000 young people in the U.K. — roughly 12 percent of all 16- to 24-year-olds — were considered at risk of becoming NEET. Each young person who fits this description will cost the U.K. economy an estimated £56,000 over the course of his or her lifetime, through lost taxes and increased dependence on public services.6 The total cost to the taxpayer is much greater when you take into account the broader social costs, including health care, homelessness, and contact with the criminal justice system.

The Department for Work and Pensions is the U.K.’s biggest public service department, responsible for welfare and child maintenance policies. It administers the state pension and a range of other benefits. In June 2011, the department launched a two-phase pilot Innovation Fund to “test new social investment and delivery models to support disadvantaged young people” by paying for outcomes that were “directly related to increasing future employment prospects.”7

The department selected ten nonprofit organizations to deliver programs as part of the Innovation Fund that would go on to serve approximately 17,000 young people over the next three years.8 This approach brought together government, service providers, and impact investors to tackle the challenges facing disengaged youth. The development of the rate card facilitated a rapid scaling of Pay for Success, enabling government to test the efficacy of diverse approaches to solving this social issue.9

DEVELOPING AN OUTCOMES RATE CARD

An outcomes rate card requires government officials to go a step further than setting policy priorities and goals. They must define how much they think those goals are worth in financial terms and determine how much they will pay for progress toward those goals. Typically, the rate card will set a payment for a number of outcomes and populations.

Governments, often working with an intermediary like Social Finance, analyze existing administrative data and define a price for each outcome, such as the value of successful entry into employment. Usually, they will incentivize certain early milestones (e.g., completion of certain levels of skills training or qualifications) that have a proven correlation with the ultimate desired outcome (e.g., entry into first employment).

Prices on an outcomes rate card may be informed by policy priorities, in addition to potential monetary savings. For example, government can use higher outcome rates to incentivize providers to focus on achieving outcomes for the hardest-to-serve populations. Service providers pick which outcomes they want to focus on, and in which geographies, rather than having to change their services to fit a single, government-mandated outcome.

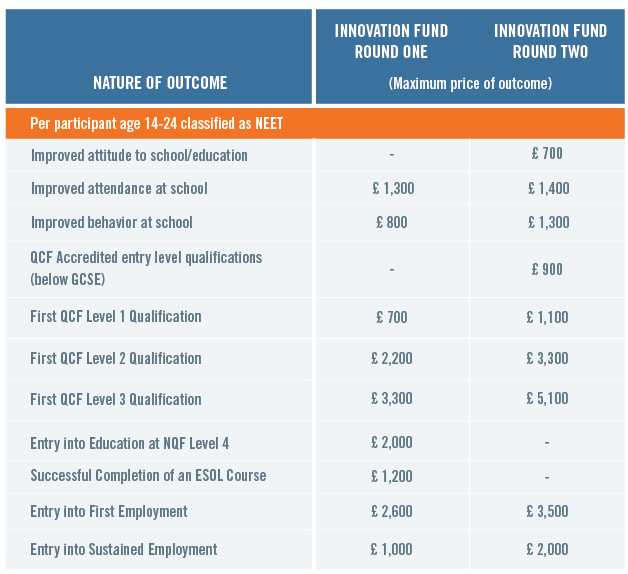

As initial results clarify which early milestones best contribute to ultimate success, and what payments attract service providers’ interest, government can tweak the rates. Figure 1 shows how the Department for Work and Pensions used this iterative approach in the second round of the Innovation Fund. Based on the first-round results, including feedback from providers and other stakeholders, the rate card in the second round increased payment rates for some outcomes and completely eliminated others.10 The importance of having an engaged service provider community that feels its full costs can be covered by achieving a portfolio of outcomes it has signed up to achieve cannot be overemphasized.

PROCUREMENT WITH AN OUTCOMES RATE CARD

Once a government has created an outcomes rate card, it begins the procurement process to select the organizations it believes can best achieve the outcomes. Impact investors and intermediaries often work with service providers to review their delivery plans, hone their bids, and provide the upfront working capital for successful bidders. Typically, investors need to fund only one-third of the total service delivery budget, because once the early-milestone outcome payments are achieved, these can be recycled to finance the later stages of the program.

The focus on outcomes represents a fundamental shift from government’s traditional fee-for-service approach. However, there are some longstanding precedents, which helped inform the development of rate cards and important improvements. Early precursors for the concept stem from New York City welfare-to-work contracts, which were launched through the Human Resources Administration in the 1990s.11 The contracts used a 100 percent performance-based model with a series of milestone payments. Today, $55 million of New York City’s newest round of Human Resources Administration welfare-to-work contracts (totaling $180 million) is allocated toward performance-based payments linked to the successful achievement of employment milestones.

In the New York City Human Resources Administration contracts, predetermined milestones drive service provider performance; outcomes rate cards combine aspects of this approach with the risk-sharing and private financing model of Pay for Success. Thus, rate cards represent a positive evolution from the performance-based contracts that preceded them, with tweaks that help address some of the challenges service providers have experienced in the past. When providers partner with impact investors to cover working capital needs, they shift all or part of the financial risk to investors. Additionally, investors provide technical assistance for providers with their rate card bids and program delivery, helping them focus on outcomes that align with their service model and enabling them to create a sustainable project budget.

Figure 1. Selected Outcome Prices from Department for Work and Pensions Innovation Fund Rate Cards12

OUTCOMES RATE CARDS AND PAY FOR SUCCESS PROJECT DESIGN

All Pay for Success projects involve detailed work to identify a target population, select outcomes, and set a value for those outcomes. But when Pay for Success projects are developed in response to an outcomes rate card, that work is front-loaded — government sets the prices, terms, and timeline before the procurement process.

Crucially, moving the process of setting outcome metrics and payment levels ahead of procurement has a powerful, positive effect on the timing of project design and service launch (Figure 2). Although the work involved in setting and pricing outcomes is similar for both the single-intervention Pay for Success model common in the United States today, and the outcomes rate card Pay for Success model used in the U.K., the former leads to one project, while the latter can yield multiple projects. Service providers, with investor support, bid specifically on their ability to deliver selected outcomes on the rate card, targeting the outcomes they are best suited to achieve. After service providers are selected, contracts are often required to be finalized within four weeks. As a result, the average timeline for an outcomes rate card project is over 50 percent shorter than the current average Pay for Success timeline in the United States.13

Although a strength of the model is its ability to standardize the Pay for Success development process, the process of rate card development must take into account the needs of the local provider community. Governments must carefully identify outcomes and prices such that they both incentivize providers to meet beneficiaries’ needs and fairly compensate providers for the cost of services.

ALIGNING OUTCOMES RATE CARD DESIGN WITH DESIRED RESULTS

Focusing on improving long-term life outcomes — but paying for early engagement, too. A well-designed rate card should have both early and late indicators and metrics, which result in payments dispersed throughout the life of the project.

Relying on strong data systems to set rates, monitor performance, and make payments. Management of outcomes rate cards requires government administrative data systems to be integrated, to analyze data and value outcomes, and to track and pay for outcomes. Data sets are also necessary to stratify rates, depending on the target population: Providers should be paid more when they achieve outcomes with harder-to-serve segments of the population, and less when they achieve outcomes with easier-to-serve segments, to avoid “cherry picking” or “cream skimming.” Outcomes rate cards will be most useful in jurisdictions with reasonably strong data systems.

Figure 2. Current Pay for Success Negotiated Development Process vs. Outcomes Rate Card Pay for Success Development Process

Using adaptive learning and feedback loops to drive better outcomes. By incentivizing providers to focus on published outcomes, rate cards create constant feedback loops. Ongoing active performance management, typically provided by a specialized third party, helps the service provider observe, diagnose, and adapt. Government can monitor effectiveness and performance.

THE PROMISE OF OUTCOMES RATE CARDS

Because of their success with at-risk youth like Jason and Emily, Career Connect and Teens and Toddlers last year became the first two social-impact-bond service providers in the world to be recommissioned to deliver a second program. The two service providers will now reach an additional 5,781 at-risk youth. Bridges Fund Management, which provided the working capital and hands-on capacity building to the two providers in the first round, was fully repaid and has signed on to provide further funding in this second round. These factors signal the early success of this iterative, outcomes-based tool for all parties involved.

In a time of rising need and shrinking resources, we need to embrace innovation and give government multiple tools with which to tackle social challenges. Outcomes rate cards provide one promising solution to drive improved social outcomes for people in need worldwide.

1 Career Connect, “Jason Moved from Unemployment to Level 2” (2016), available at https://www.careerconnect.org.uk/Jason-moved-from-unemployment-to-Level-2-c1.html.

2 Richard Garner, “Teenagers’ Exam Results Boosted Through Scheme Pairing Them to Work with Small Children,” Independent (August 20, 2015), available at http://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/teenagers-exam-results-boosted-through-scheme-pairing-them-to-work-with-smallchildren-10463801.html.

3 U.K. Parliament, “NEET: Young People Not in Education, Employment or Training,” Research Briefing (2016), available at http://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/SN06705#fullreport.

4 For more information on Career Connect see https://www.careerconnect.org.uk.

5 For more information on Teens and Toddlers see https://www.teensandtoddlers.org.

6 Bob Coles et al., “Estimating the Life-Time Cost of NEET: 16–18 Year Olds in Education, Employment or Training: Research Undertaken for the Audit Commission,” University of York (2010).

7 Cabinet Office: Centre for Social Impact Bonds, “Department for Work and Pensions Innovation Fund,” available at https://data.gov.uk/sib_knowledge_box/department-work-and-pensions-innovation-fund.

8 Emily Gustafsson-Wright, Sophie Gardiner, and Vidya Putcha, “The Potential and Limitations of Impact Bonds: Lessons from the First Five Years of Experience Worldwide,” Brookings Institution (July 2015), available at https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Impact-Bondsweb.pdf.

9 A note on terminology: We will use “Pay for Success” as an umbrella term to describe government human services or health system contracts commissioned on an outcomes-focused basis. By “social impact bonds” (the more common term in the United Kingdom), we mean the subset of Pay for Success projects (Pay for Success financings), where a social or impact investor provides the upfront working capital to social sector organizations delivering the program.

10 Rita Griffiths, Andy Thomas, and Alison Pemberton, “Qualitative Evaluation of the DWP Innovation Fund: Final Report,” Department for Work and Pensions (July 2016), available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/535032/rr922-qualitative-evaluation-of-thedwp-innovation-fund-final-report.pdf.

11 Swati Desai, Lisa Garabedian, and Karl Snyder, “Performance-Based Contracts in New York City Lessons: Learned from Welfare-to-Work,” Rockefeller Institute (June 2012), available at http://www.rockinst.org/pdf/workforce_welfare_and_social_services/2012-06-Performance-Based_Contracts.pdf.

12 HM Government, “Innovation Fund: Key Facts” (2017), available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/212328/hmg_g8_factsheet.pdf; Cabinet Office: Centre for Social Impact Funds, “Department for Work and Pensions Innovation Fund,” available at https://data.gov.uk/sib_knowledge_box/department-work-and-pensions-innovation-fund.