Building a Market for Health: Achieving Community Outcomes Through a Total Health Business Model

Jewel, eight, clasps her mother’s hand as they enter the hospital elevator. As the doors slide shut, she manages one last peek at the brightly colored murals of the fifth-floor pediatric unit. Her mother, Elena, 30, squeezes Jewel’s hand, anxiously fretting that she must do more to manage Jewel’s weight and increasing risk of diabetes. Jewel’s doctor has warned that if she doesn’t eat better and move more, she must soon start on metformin or risk the fate that Elena herself could not avoid — type II diabetes and early cardiovascular disease.1

As the elevator drops to street level, Elena’s mind races for a solution. A single parent, working more than 50 hours per week as a hairstylist, her income barely covers the rent and utilities of their one-bedroom apartment in a neighborhood long characterized by disinvestment. There is no full-service grocery store in their neighborhood, and though the corner store recently introduced a limited selection of fresh produce, the higher costs and longer preparation times make regular, healthy meals more of a distant goal than a daily reality. Meanwhile, her attempts to get Jewel out to play involve two bus transfers to the closest park and recreation center, which she can reasonably manage only about once per week. But Elena prioritizes this critical activity time, as it is unsafe for Jewel to play near the tough streets of their transitional neighborhood, and walking or riding a bike to school or other activities on busy roads without sidewalks is both dangerous and impractical.

When the doors slide open on the ground floor, Elena and Jewel step back into their daily lives, presented with a challenge confronting tens of millions in America today: how to achieve health in an environment that seems to conspire against it. Despite her mother’s best intentions and efforts, at this rate, Jewel is likely to experience a future characterized by increased stress, declining physical health, reduced quality of life, and significant medical care procedures — at a financial cost that will only further exacerbate her stress. Indeed, unless policymakers, investors, civic leaders, and advocates working across sectors can reform and invest in the systems that produce health in the first place, our nation will likely see such personal challenges continue to drive the decline of population health, and the demand for costly health care services. While increasing spending on care services can be wildly profitable to private-sector entities in the business of sick care, these same profits are making health care more unaffordable for most Americans every day.

To contain costs and change the odds for Jewel and other families with adverse community experiences across the nation, we must reorient our health and social systems upstream, toward the outcome of total health, rather than focusing ever more resources on downstream clinical care interventions. By employing health-outcomes-focused policies, practices, and investments, many of the disease conditions our nation is battling could be avoided, along with their attendant costs. In a capitalist democracy, this calls for building a marketplace that values improvement in health outcomes, as an alternative to the existing marketplace that primarily rewards the volume of health care services provided. A marketplace for health outcomes would supply community members with the social, economic, and environmental conditions that produce longer, stronger, and healthier lives. Over time, such a market could reduce preventable demand for costly care services, making access to care more affordable for all Americans.

As an increasing number of health systems begin to explore value-based “at risk” payment arrangements and more fully embrace their stated missions to be accountable for the health of their communities, they are recognizing the benefits of a marketplace that values health. Indeed, some of these health systems are transforming their business models to move from volume (of care services) to value (of outcomes produced). They are increasingly investing in, and working in close partnership with, schools, low-income housing providers, local healthy food cooperatives, community development corporations and other “health-producing” community organizations — both to realize better health outcomes and to reduce unnecessary use of expensive care services that drive up avoidable costs.

A NATION AT RISK

Access to health care services is an essential human necessity, and continuing to ration access to health care by wealth or selected demographic group is untenable. Ensuring that everyone has access to a “medical home” — a regular and ongoing place that cares for his or her health and wellbeing — is both a moral imperative in a just society and a wise investment. While only ten to 20 percent of health outcomes are attributable to access to health care services, access to care contributes to increased wellbeing and functional health status, as well as to managing long-term costs. Expanding access for all Americans, especially to primary care and preventative services that integrate mental and physical health, promises to both improve health outcomes and contain preventable demand driven by costly illnesses in the first place.

America’s treatment-oriented health care system comes at significant expense to the taxpayers, employers, and insurers who pay for it. These costs are only increasing. In 2015, national health expenditures accounted for nearly $3.2 trillion, or 18 percent of the gross domestic product (GDP).2 These expenditures exceed 20 cents of every dollar when including the indirect costs associated with diminished worker productivity, tax revenue losses, and the significant emotional and psychological toll that illness takes on individuals and their families. Health care spending as a percentage of GDP is now twice the rate of what it was in 1980 (8.9 percent) and three and a half times that in 1960 (5 percent).3 The rising supply-driven costs of pharmaceuticals, medical technology, and biotech devices further drive the growth of health delivery expenditures.

High and rising health care costs in a market that values treatment crowds out investments with higher potential to promote health and wellbeing. Nearly three-quarters of total U.S. health care expenditures are attributable to chronic disease, including those suffering with complex mental and behavioral health conditions. Much of this can be prevented by more effectively addressing an inextricably connected blend of economic, environmental, social, and cultural factors that influence health.

A growing body of research shows that health outcomes are more directly shaped by economic, social, and environmental determinants within communities than by care services.4 As such, initiatives that focus on resilient and equitable community development — safe affordable housing, active and accessible transportation options, healthy and affordable food, economic opportunity, and quality education, particularly in historically disinvested communities where health outcomes tend to be worse and threats of climate change are greatest — are critical, upstream drivers of health. Deeper investments in these non-health-care drivers of health outcomes are needed to improve health outcomes and slow the growth of health care costs.

Making these kinds of upstream investments and policy changes to improve population health outcomes will require a significant shift in both how we think about health and who plays a role in creating it. It calls for looking beyond the doctors, nurses, and care providers who address existing ailments and engaging the leaders in business, education, finance, and civic life, who can help prevent them in the first place. There are many complementary benefits in this equation, as the primary factors that shape health outcomes are the same ones that drive economic opportunity: equitable access to education, housing, transportation, and healthy foods, reducing stress and improving public safety, etc.5 But for this leadership shift to happen, the health care sector must increasingly work closely with leaders in the finance and civic sectors to make these investments.

SHIFTING FROM HEALTH CARE SERVICES TO HEALTH OUTCOMES

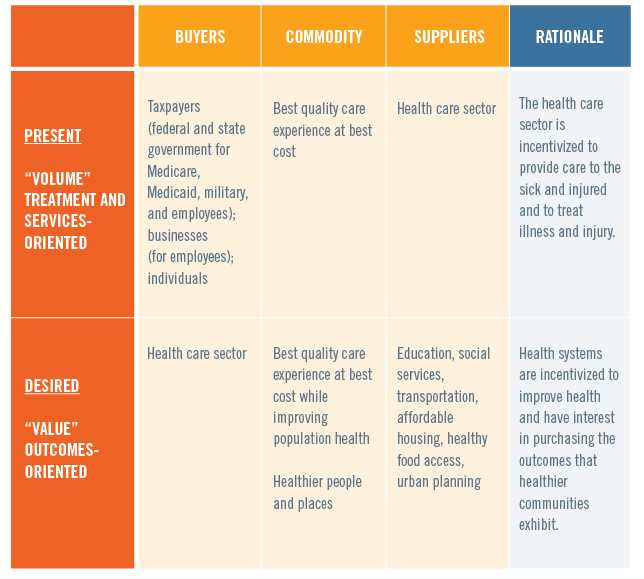

In the current health care marketplace, private and public insurers “supply” health care coverage to “buyers” — the people and businesses that purchase it. In the case of Medicare, Medicaid, and for the military, the supplier is the U.S. government. By offering products that spread risk, coverage makes health care more affordable and accessible to consumers and ensures that care providers (physicians and health systems) are paid fairly for the critical services they deliver.

In this volume-centric system, resources are primarily applied to health care interventions (e.g., treatment for chronic disease conditions, such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and mental health disorders). This model, rewarding treatment rather than wellness, does little to incentivize improved health outcomes or cost containment. Even physicians’ admonishments to their patients to change behaviors related to diet, exercise, and stress management often translate to little more than well-wishes, as there is little reward or accountability for assuring long-term health outcomes.

Also, in this volume-centric system, investments in the upstream determinants of health outcomes are not rewarded and, as such, are inadequately produced and delivered at a level sufficient to result in significantly better health outcomes. Furthermore, in a nation that tends to privatize gains while socializing costs and underestimating risk, funding for these health determinants is undervalued as a benefit to society, and as a result is woefully inadequate to address existing needs. Federal spending on Medicare alone exceeds both mandatory and discretionary federal spending on food assistance, transportation, housing, education, and unemployment programs combined.6 Yet these nonmedical drivers of improved health outcomes and lower care costs over time are the top challenges identified in Community Health Needs Assessments. This result points to both a market failure and a market opportunity.

The health care sector is well positioned to unlock new sources of capital by helping to shift the health economy from its primary current focus on providing health care services to a concurrent focus on generating improvement in population health outcomes. In a new marketplace for health that seeks a return on increasing health and wellbeing, the actual “producers” of healthy people and environments (educators, land use planners, transportation agencies, affordable housing developers, food producers, and community development finance institutions) would supply health-promoting conditions to “buyers” of total health — the health care-sector actors (insurers, providers, integrated delivery systems, etc.) that are seeking to improve health outcomes and lower preventable spending for care delivery.7

In this new marketplace, the health care sector leverages and redirects existing and future assets to invest in community development factors that affect health outcomes. By investing in what gets and keeps people healthy, the sector is poised to increase health outcomes and, with time, reduce spending on unnecessary treatment and care. In this new health marketplace, health care systems “at risk for health” will increasingly value what community development institutions produce as purveyors of health. Under ideal market conditions, increased demand will boost supply and generate competition that creates equitable opportunity and access to the American Dream in the form of quality education, living-wage incomes, housing, food, transport, human connection, and the potential to build household wealth.

Opening this new marketplace for health will provide opportunities for a variety of actors to contribute to improving overall population health outcomes. Market mechanisms will create avenues for philanthropy, financial institutions, and others to work in coordination with community developers to augment the quality and volume of their “products.” These mechanisms will also create roles for toolmakers and intermediaries across fields — from predictive data analytics to a continuum of nonmedical community health workers — to help translate the health demands and needs of “buyers.” This marketplace can also spark innovation among smaller and local entrepreneurs to meet the increased demand for health by employing business models that create healthy community environments and behaviors.

Figure 1. Health and Health Care / Supply and Demand

PROFILE OF AN EARLY ADOPTER: KAISER PERMANENTE

Kaiser Permanente (KP), the nation’s largest nonprofit integrated health system ($61 billion in revenue in 2015), provides both care and coverage. That is, KP offers its 10.6 million members across eight states and the District of Columbia both competitive insurance plans and care from more than 20,000 physicians. This structure incentivizes the organization not only to treat and care for existing and developing medical conditions, but also to help keep members from getting sick in the first place. KP seeks to make care and coverage more affordable by improving health and reducing preventable utilization, thereby increasing quality and managing costs.

As a mission-driven organization, the business challenge KP faces is that it is “at risk” for 100 percent of the health of its members, but as a provider of care services, it directly produces only ten to 20 percent of what creates health in the first place. In other words, KP as an insurer is accountable for covering the costs of Jewel’s medical treatments, but by itself as a care provider, at first glance, it can do little more than effectively treat her worsening conditions, and support her in practicing healthier behaviors. Ultimately, the organization is at risk for that which is primarily outside of its direct control. This is similarly the case for any health care provider that enters into an at-risk or value-based risk-sharing arrangement. So to promote health, prevent disease, and manage conditions, care organizations need community partners.

As such, investments in resilient, equitable community development that create health have tangible value for KP, other insurers, and care providers increasingly engaging in at-risk arrangements. By promoting access to affordable housing, active transportation options, better schools, healthier and more affordable food, and safer communities — i.e., the social determinants of health — these health systems are increasingly able to address the 80-percent-plus nonclinical determinants of health; they are also better able to deliver on their mission to provide high-quality, affordable care and to improve the health of the communities they serve.

Recognizing this opportunity, KP has worked to creatively seek out and invest in healthy community strategies for the total health of its members. In effect, it has become a “buyer” of health in the marketplace for health.

- In Oakland, CA, leadership at KP is working closely with the mayor, city and county councils, school district, other health systems, foundations, and civic leadership via the Oakland Thrives Leadership Council to make a generation-long commitment to health, education outcomes, and equitable prosperity.

- In 2006, KP helped to found the Convergence Partnership, a collaboration of foundations and health systems aiming to accelerate a vision of healthy people and places by leading and supporting fundamental shifts in policy and practice across sectors. In more than a decade of strategic partnerships with government and nonprofit organizations, network- and capacity-building among foundations across the country, policy advocacy, and shared grantmaking, the partnership has influenced significant federal, state, and local policy changes related to healthy food financing, transportation equity, and resilient, equitable development.

KP has also recognized its role as a community anchor institution in and across its eight states and the District of Columbia.

- In 2015, $1.7 billion of a total of $20 billion of KP’s purchasing nationally was made to women and minority suppliers. KP’s national supplier diversity team is now working to localize that spending, creating local jobs and circulating wealth-creating resources in its footprint.

- KP’s environmental goals aim to reduce the impact of its operations on population health. In recent years, this includes meeting over 50 percent of total energy needs with renewable sources, facilitated by an $800 million investment in solar and wind generation, creating green jobs and setting the pace for the health sector.

- KP has set up more than 60 farmers’ markets in its communities — often at care facilities, for ease of access for employees and the community — as part of its efforts to deliver total health, leveraging all organizational assets and resources.

- Other total health levers at KP include workforce pipeline development into vulnerable communities, impact investing, and designing facilities and surroundings as drivers of vibrant places (e.g., placemaking)8 that spark economic development and human connection.

GETTING THERE

Delivering significantly improved population health outcomes at significantly decreased costs will require a deliberate, long-term agenda that scales up the “dose” of health promotion and healthy communities. This must be core to the work of all nonprofit health systems with missions that call them to improve community health, not just those currently able to capture the economic benefit. Results from years of efforts in community benefit have led KP researchers to understand that the reach of an initiative (how many lives it touches), together with the intensity (strength of intervention) and duration (length of intervention), directly influence the initiative’s impact.9 In the marketplace for health, higher “dose” can be achieved through greater supply of, and demand for, the economic, social, and environmental determinants of health. Increased investment in resilient, equitable community development, greater and more diverse collaborative leadership, and a focus on low-income people, rural communities, and communities of color can substantially reduce disease rates.

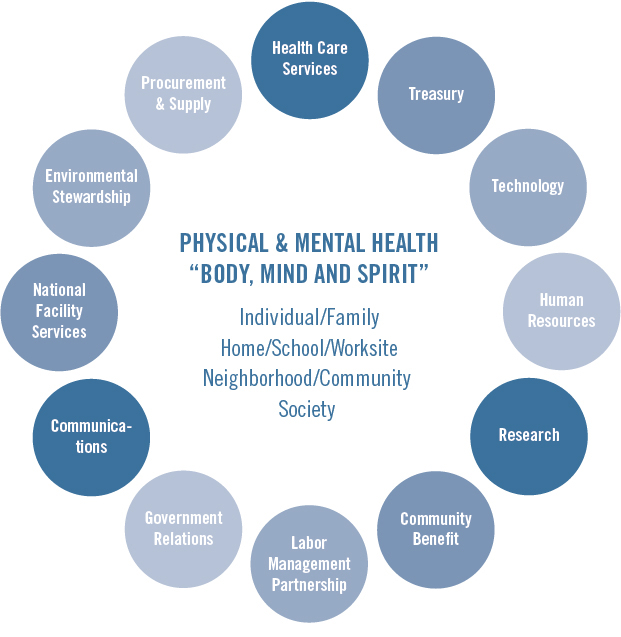

Figure 2. Total Health Impact: Leveraging Multiple Assets at KP

One promising avenue to boost supply of health value production is through health systems (as well as universities, governments, and large employers rooted in place) acting as anchor institutions in their communities. “Anchor institutions” — often the universities and hospitals in a city or region — wield significant power as engines of local economic growth and revitalization, and they have massive opportunity to deliver on community wellbeing and prosperity objectives.10 Anchor institutions are usually the largest employers in their locales, with sizable human resource needs that can help to build out local workforce pipelines and training and career development opportunities for disadvantaged populations and workers across fields and skill levels. The fixed and expansive size of their footprints typically includes building and development demands that can lead to creative placemaking and fuel local construction trades. Their purchasing power in combination with the demands of their operations, when procurement is localized, can drive powerful wealth-multiplier effects across regions. Investing their pension funds and capital reserves for direct impact on the economic, environmental, and social determinants of health (from housing as a platform for health to healthy food and clean-energy enterprises that concurrently create local green jobs and wealth creation) can bring much-needed resources to places and sectors that have experienced disinvestment and that disproportionally contribute to chronic disease, mental health, and reduced economic opportunity.11 For many leading health systems such as KP, community benefit work that initially led to healthy eating and active living initiatives, has expanded to an emphasis on policies, systems, and environmental changes, as well as prevention. As health sector leaders immerse themselves more deeply in this upstream work, dozens of health systems are coming to recognize that increasing dose also requires harnessing the full power of hospitals and health systems as community anchor institutions.12

Another primary avenue for improving outcomes is through collaboration for clinical-community integration, especially around meeting the nonmedical (economic and social) needs of patients, from food security to affordable housing. This will require collaboration between health care providers and other anchor institutions (including banks, community development finance institutions, transportation, and housing) at a scale never attempted before. It will mean investing deliberately in the upstream public, nonprofit, and philanthropic capacities that advance healthy environments. It will mean building robust feedback loops for learning across fields and sectors about the social and economic environments that influence health.

One of the too-often-overlooked benefits of the Affordable Care Act is the important payment mechanisms and incentives for health care providers to move from volume (of care services) to value (for delivering health outcomes) via risk-sharing arrangements and global payments for defined populations. As such, hospitals and health systems and physicians are beginning to move toward an incentive model to deliver the best-quality care experience, at the best cost, while improving population health (the aptly named “triple aim”).13 In any reform scenario for the Affordable Care Act, it is vital that value-based incentives for providers to produce better outcomes at less cost are not only preserved, but expanded.

THE PROMISE OF AN OUTCOMES-BASED APPROACH TO HEALTH: THREE CALLS TO ACTION

A market that values health incentivizes an outcomes-based approach to improve Americans’ health while reducing preventable use of health care services. By increasing health outcomes and making care more affordable, this approach also leads to increased family and community prosperity and security. Advancing this approach through cross-sector collaboration can serve as a boundary-crossing salve to the toxic partisanship that often thwarts meaningful progress on the contributors to population health and equitable economic opportunity. We offer three calls to action:

- Civic leadership and accountability. Creating a marketplace for health that measurably improves outcomes will require significant conversations and actions on complex social issues, engaging leaders across sectors and diverse communities to move from doing good things to being accountable for results. This means setting a table that engages both traditional leaders — the politicians, executives, and civic leaders whose institutions can significantly impact community outcomes — and nontraditional community leaders who shape the social, cultural, and economic landscapes of our communities. This must include residents with innate expertise and lived experience in the viability of potential improvements to community conditions; educators and service providers intimately acquainted with local needs and assets, taking trauma-informed approaches; and the advocacy and philanthropic organizations that are fueling social change. Professionals deeply engaged in shaping the form and function of communities — transportation and land use planners, affordable housing developers, real estate investors, community development finance institutions, banks, and so on — must also have a voice. Civic discourse must be strong enough and long enough to match challenging, longer-term forces at play in communities, such as gentrification, displacement, and persistent, concentrated poverty in urban and rural areas. To create a sustainable infrastructure of health and opportunity, this work must transcend election cycles, grantmaker initiative periods, organizational timeframes, and generational divides to meaningfully address the health conditions that manifest across lifetimes and persist across generations.

For health systems, this means stepping up to the civic table with other leaders across sectors to identify roles and opportunities for driving equitable community development strategies that produce health. For nonprofit, mission-driven health systems, this work is essential to delivering on their stated commitment to measurably improve health in the communities they serve. - Health in all investments, policies, and practices. Advancing total health outcomes will require fearlessly and relentlessly improving our organizational practices and policies and making necessary investments at a sufficient scale. We must ask whether and how every operational decision affecting the economy, society, and the environment can contribute to positive health outcomes.

For health systems, this means embracing the triple aim of a high-quality care experience, cost reduction, and creating healthier people and communities; making the assessment of and referral to basic human needs a standard of care; and embracing health care’s role as an anchor institution with significant economic leverage. - Innovating, tracking outcomes, learning. Continually improving results will require better (more timely, transparent, granular, accessible) real-time data and predictive analytics to understand and act on the complex interplay between the economic, social, and environmental issues facing our communities. This requires a disciplined focus to generate, assess, and learn from actionable information and to share results in a way that builds understanding, accountability, and action. It means disaggregating data by race and other socioeconomic factors to understand disparities in impacts and investments, and how such disparities might (or might not) align. This information should always inform strategies and partnerships.

For health systems, this means leveraging existing resources (such as Community Health Needs Assessments), building new partnerships (with community development organizations and other anchor institutions to share existing data and generate shared data), and innovating on data collection, analysis, and reporting in creative and intentional ways (through improved efforts around learning, measurement, and assessment).

By partnering with the health sector, community development leaders and those who finance their activities hold the greatest promise for improving population health, reducing preventable costs, and paving the way to a healthy, more equitably prosperous nation. Given that economic and social factors are the primary drivers of health outcomes, a community development approach to health can be coupled with deeper investments in disease prevention and clinical-community integration to reduce preventable use of services and, in turn, reduce demand-driven care costs. This is a call to leadership to accelerate the transition from volume to value, and from a market that primarily values health care services to a market that primarily values and rewards health outcomes. A market that values health is America’s key to unleashing the innovation and investment that can create more affordable health care — and better health for all.

Jewel, now 30, releases her daughter Leticia’s hand as they approach the sidewalk from the crosswalk, where cars and bikes anticipate the walk signal. Giggling, eight-year-old Leticia dashes past the storefront of the hair salon that Jewel owns and manages to the community play lot on the far corner, where she marvels at the brightly colored new mural on the building wall. From the fresh produce market across the street, her grandmother Elena, 52, shouts and waves hello. The incredible changes she has seen in this neighborhood over the past 22 years have made all the difference for her granddaughter. Leticia might never know of the many difficult but critical investments and policy changes that community leaders made two decades before; she may also never know of the daily challenges that childhood obesity and chronic disease can bring over a lifetime.

1 This vignette of Elena and Jewel (not their real names) is adapted from composite archetypes of patients’ lives and care experiences.

2 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditure Data” (2016), available at http://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nationalhealthaccountshistorical.html.

3 Ibid.

4 Sandro Galea et al., “Estimated Deaths Attributable to Social Factors,” American Journal of Public Health 101 (8) (2011): 1456–1465, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3134519/. Finds that the number of deaths attributable to social factors in the United States (low education, racial segregation, low social support, individual poverty, income inequality, area-level poverty) is comparable to the number attributed to pathophysiological and behavioral causes.

Ali H. Mokdad et al., “Actual Causes of Death in the United States, 2000,” Journal of the American Medical Association 291 (10) (2004): 1238–1245, available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15010446. Estimates that approximately 45 percent of deaths in the United States in 2000 were attributable to preventable ailments caused by tobacco use, poor diet, and physical inactivity, alcohol consumption, microbial agents, toxic agents, motor vehicle crashes, incidents involving firearms, sexual behaviors, and illicit use of drugs. Other unquantifiable causes of death included socioeconomic status and lack of access to medical care.

J. Michael McGinnis and William H. Foege, “Actual Causes of Death in the United States,” Journal of the American Medical Association 270 (18) (1993): 2207–2212, available at https://galileo.seas.harvard.edu/images/material/2800/1140/McGinnis_ActualCausesofDeathintheUnitedStates.pdf.

5 Michael Marmot and Richard Wilkinson eds., Social Determinants of Health: The Solid Facts, 2nd ed. (Denmark: World Health Organization, 2003).

6 National Priorities Project, “Federal Spending: Where Does the Money Go,” available at https://www.nationalpriorities.org/budget-basics/federal-budget-101/spending/; Juliette Cubanski and Tricia Neuman, “The Facts on Medicare Spending and Financing,” Kaiser Family Foundation (July 2016), available at

http://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/the-facts-on-medicare-spending-and-financing/; Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “Policy Basics: Non-Defense Discretionary Programs” (February 2016), available at

http://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/PolicyBasics-NDD.pdf.

7 The typology of this market into “buyers of health,” “sellers,” and “connectors” was developed by Ian Galloway, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, for the SOCAP Health conference in 2013. For more details on that conference, see the agenda and other content at http://www.frbsf.org/community-development/events/2013/september/socap-social-capital-markets-health/.

8 Project for Public Spaces, Inc., “Improving Health Outcomes Through Placemaking” (2016), available at https://www.pps.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Healthy-Places-PPS.pdf.

9 Pamela Schwartz, Suzanne Rauzon, and Allen Cheadle, “Dose Matters: An Approach to Strengthening Community Health Strategies to Achieve Greater Impact” National Academy of Medicine (August 2015), available at https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Perspective_DoseMatters.pdf; Pamela Schwartz, “Lessons Learned from Kaiser Permanente’s Community Health Initiative (CHI) Evaluation,” Kaiser Permanente (2014), available at https://share.kaiserpermanente.org/article/building-the-field/.

10 Tyler Norris and Ted Howard, “Can Hospitals Heal America’s Communities?” Democracy Collaborative (December 2015), available at http://democracycollaborative.org/content/can-hospitals-heal-americas-communities-0.

11 Enterprise Community Partners, “Health & Housing” (2017), available at http://www.enterprisecommunity.org/solutions-and-innovation/health-and-housing; East Bay Asian Local Development Corporation, “Healthy Neighborhoods” (2015), available at http://ebaldc.org/healthy-neighborhoods; Emerald Cities Collaborative, “Oakland Programs and Initiatives” (2017), available at http://emeraldcities.org/cities/oakland; Great Communities Collaborative, “Impact” (2017), available at http://www.greatcommunities.org/our-work/impact.

12 Nancy Martin, “Advancing the Anchor Mission of Healthcare,” The Democracy Collaborative (March 8, 2017), available at http://democracycollaborative.org/content/advancing-anchor-mission-healthcare-report.

13 Institute for Healthcare Improvement, “The IHI Triple Aim” (2017), available at http://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx.