Better Outcomes for Chronically Homeless “Frequent Users”

Allen was living on the streets of San Jose for more than six years. He occasionally slept in shelter beds when they were available but more frequently stayed under freeway overpasses. He had an extensive history of incarceration, cycling in and out of jail in his home state of Colorado, typically after parole violations. He was eventually given a bus ticket to California, and he arrived in Santa Clara County with no resources, no social networks, and a criminal history that prevented him from finding work. Shortly after arriving, he was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder. He also suffers from serious arthritis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which were compounded by his extended homelessness. With a mostly untreated mental health disability and numerous acute medical conditions, he was hospitalized 15 times in two years but remained homeless during that time. He was placed in permanent supportive housing as part of Project Welcome Home (PWH) in September 2015. Since then, he has received regular medical and mental health care, taken scheduled medication, and attended weekly respite support groups. He has remained stably housed and re-established a relationship with his son (from whom he had been estranged for 18 years). His hospitalization rate has decreased sharply.

In Santa Clara County, there are more than 2,200 chronically homeless people living on the streets at any point in time, of whom more than 90 percent are unsheltered.1 Like Allen, many receive a fragmented and inconsistent array of services from the county’s emergency system, and some cycle in and out of jail. Without a safe, permanent place to live, they remain disconnected from the comprehensive, coordinated care they need to address their physical and mental health issues. This is not just an inhumane situation; it is a costly one. According to a study commissioned by the county in 2015, the costs associated with a chronically homeless person cycling through their emergency systems can exceed $83,000 per year, without actually ending that person’s homelessness. By contrast, well-designed permanent supportive housing costs much less (under $20,000, in some cases) and, more important, significantly reduces human suffering.2

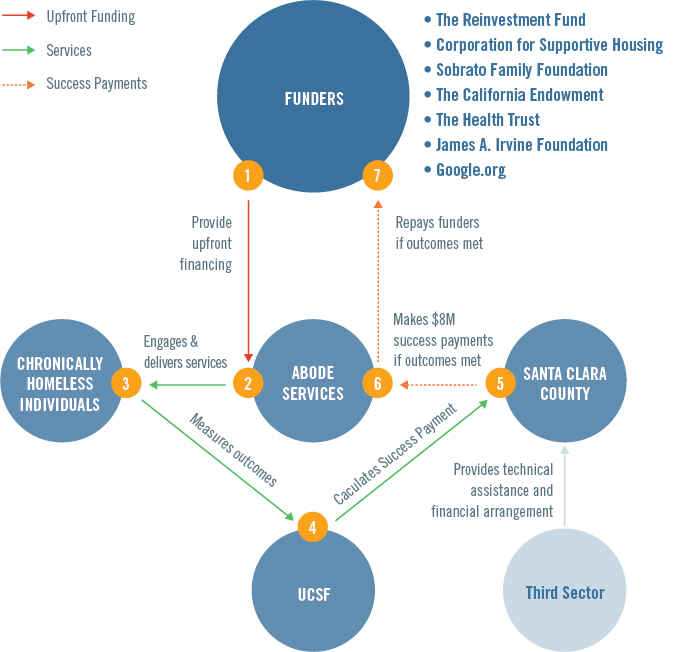

At Abode Services, we are familiar with the immense benefits of permanent supportive housing for the people we serve. We provide housing to roughly 1,100 people on any given night through our various housing programs and have seen the incredible improvements that people can make in their lives when connected to a safe, stable place to live. When we learned that the county wanted to try the Pay for Success model within a permanent supportive housing program, we were immediately attracted to the opportunity. The idea was that rather than pay us directly to connect chronically homeless people to permanent supportive housing, the county would define the success that it expected from our work, a group of investors would pay us the real cost of meeting those success targets, and the county would pay back the investors only when we reached them. In some cases, the “success payments” to investors were calculated to include modest returns that would be realized only if the program was fully successful. Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) would evaluate the project’s success.

Some of the benefits were very clear. The county would pay only for programs that worked. And investors could make a socially responsible investment in a complex social problem and generate a modest return. As the service provider, we saw the possibility of bringing our track record of successful permanent housing programs to greater scale while getting paid for the full cost of running the program, instead of relying on a barebones budget so common in nonprofit contracting.

Another appealing feature for Abode was that, unlike many other Pay for Success models, we did not need to prove that our intervention saved the county money directly in order to be deemed a success. The county was confident that permanent supportive housing would be more cost-effective than providing emergency services on an irregular basis. As such, for the purposes of triggering repayment to the investors, success would be defined as housing stability alone. The UCSF evaluation would also assess reductions in service utilization, but those were ancillary outcomes. That was a big selling point for us — we wanted to rely on success metrics that we had used before and according to which we had already demonstrated success.

One of the initiative’s larger benefits was that it offered a concrete and visible representation of the county’s growing commitment to performance measurement within its larger system of homeless service delivery. Faced with limited resources, the county increasingly focused on measuring performance at both the program level and system level and wanted to invest resources in the interventions that had the greatest impact.

The deal construction was like no other contract negotiation Abode Services had ever participated in. It took nine months to carefully determine the success metric, develop project budgets, attract and secure investors, and develop and enter into legal agreements. In the end, project investors were local and national foundations (Google.org, Sobrato Family Foundation, Health Trust, The James Irvine Foundation, California Endowment, Laura and John Arnold Foundation), national community development financial institutions (The Reinvestment Fund, Corporation for Supportive Housing), and Abode Services in the form of at-risk deferred program fees. It was also determined that Abode Services would not only manage the program but would play the Pay for Success manager role, which in previous deals was the responsibility of a third party. In this role, Abode Services handles all project finances and convenes a quarterly meeting of the investors to report on project metrics.3

After winning a competitive bid process and working through a nine-month deal construction period, PWH was launched. PWH combines permanent housing (in site-based and scattered-site apartments) with wrap-around supportive services — such as outreach and engagement, intensive case management, and specialty mental health services (offered according to the Assertive Community Treatment model) — for 112 chronically homeless people at any point in time. At the time of writing, Abode was nearing month 16 of operations, with all 112 people placed in housing.

Figure 1. Santa Clara Pay for Success Overview

The PWH team has thus far met the housing stability targets built into the first five quarters of success projections and has generated the projected amount of success payments for investors. We know that long-term housing stability for chronically homeless people can take years in some cases, but we are cautiously optimistic that the program’s success will continue. We are hopeful not just that the project investors will be repaid, but that housing stability and the reductions in service utilization will provide a solid evidence base for the county to continue to invest in permanent supportive housing. In that sense, the Pay for Success model has provided a great opportunity for Abode to do more of what we know works and, in partnership with the county, broadcast that success to generate additional support and investment. We are grateful for the opportunity.

That said, the model does have some drawbacks, which any interested service provider should consider before diving in. We have spelled out some of those challenges below, not to discourage prospective providers, but with the hopes of preparing them for the journey ahead.

Prepare for a sizable investment of staff time and resources. Government contracting is often unilateral. Local governments tell service providers what they expect and how much they will pay. However, there is no such simplicity or clarity in Pay for Success deal construction, and our team had to weigh in at every turn. This was empowering and likely resulted in a program design that truly served us. But it also meant that our agency leadership had to be available, capable of tracking several complex deal elements at the same time, and comfortable making very important decisions with little time to reflect. In addition, our deal involved multiple investors who came to the table at different times, each with unique expectations and due-diligence needs. Any organization considering a Pay for Success deal should ensure that there is a relatively high-level staff member who will devote 60 to 80 percent of his or her time to deal construction for several months.

Greater efficiencies are needed with respect to defining success. How a local government defines success and the degree to which a group of investors will agree with the rigor and/or reasonableness of that definition both depend on who is sitting at the deal construction table. As a provider of permanent supportive housing, we believed that the case for our success in the field was well established. We have been measuring and reporting our program outcomes according to U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development standards for years. However, our investors wanted a finer-grained success metric, which meant that we had to rely on a measure that we had never used before. This was harrowing for us, as we did not want to agree to something that we were not sure we could achieve. To confirm that we could, we chose to pull individual client records manually and test the proposed measure, which was arduous and time-consuming. Ultimately, Pay-for-Success-funded programs should have similar definitions of success; otherwise, economies of scale or efficiencies will not be attained as more deals are finalized.

The politics of negotiation can place service providers in an uncomfortable spot. When it comes to setting the success target, there is an inherent tension between the imperatives of the local government funder (who wants to pay only for true success) and those of the investors (who want to be sure that they get paid back). Each entity has its own risk calculation. The reputational risk assumed by the service provider is often ignored in this negotiation. If the target is too low, the provider looks unimpressive, but if the bar is too high, the provider can do an excellent job but still look like a failure. In our case, the county initially proposed a success rate that we did not believe was attainable, but one of the potential investors countered with a rate that would have been embarrassingly low. This uncomfortable position required us to respectfully stand up to our local government partner — and to a table of financial and philanthropic institutions — and assert a target that we thought was reasonable but challenging. Without strong agency leadership, excellent relationships with our funders, and confidence in our data, success negotiations may not have turned out as well.

There is not yet full fidelity to the model and spirit of Pay for Success. In theory, Pay for Success shifts the role of local government from bureaucratic contract management to performance measurement. Investors ostensibly enter the deal when their due-diligence demands are satisfied, then retreat to the background and wait for their success payments to start flowing in. Reality and theory are not totally aligned just yet. We learned from our deal that local government agencies — and some funders — still feel the need to closely manage the budget and other operational elements of the program, in the spirit of being responsible stewards of public funds. As understandable as this may be, our reporting requirements have doubled, with the standard reporting requirements (of which we were supposed to be free) now layered on top of the new, more intensive, reporting requirements associated with program success. And our investors remain closely involved, regularly attending monthly meetings, monitoring our housing placements, and at times asking for additional reports. In sum, a number of the philosophical elements of the Pay for Success model have not translated into program operations. As such, any service provider contemplating involvement in Pay for Success should build into the program the bandwidth to satisfy these additional reporting requirements, at least until investors and government funders are more comfortable with the model.

The Pay for Success model is still very new. Only a handful of Pay for Success programs are operational, and only two have reached a point where program success or failure can meaningfully be measured.4 Our program is in its initial stage, and the conclusions we draw five years from now will likely differ from those reflected here. In addition, as the field grows, we are likely to see many more lessons learned, improvements, and efficiencies. In the meantime, for providers who are thinking about diving into these relatively uncharted waters, it is our hope that these observations and recommendations help to inform your decision and ensure your success.

1 Applied Survey Research, “Santa Clara County Homeless Point-In-Time Census & Survey” (2015), available at https://www.sccgov.org/sites/oah/coc/census/Documents/SantaClaraCounty_ HomelessReport_2015_FINAL.pdf.

2 Kaitlyn Snyder, “Study Data Show that Housing Chronically Homeless Peoples Saves Money, Lives,” National Alliance to End Homelessness, available at http://www.endhomelessness.org/blog/entry/study-data-show-that-housing-chronically-homeless-people-saves-money-lives.

3 Nonprofit Finance Fund, “Project Welcome Home” (2017), available at https://nff.org/invest-in-results.

4 Donald Cohen and Jennifer Zelnick, “What We Learned from the Failure of the Rikers Island Social Impact Bond,” Nonprofit Quarterly (2015), available at https://nonprofitquarterly.org/2015/08/07/what-we-learned-from-the-failure-of-the-rikers-island-social-impact-bond/; Jeff Edmondson et al., “Pay-For-Success is Working in Utah,” Stanford Social Innovation Review (2015), available at https://ssir.org/articles/entry/pay_for_success_is_working_in_utah.